Last week, I talked about memorizing music and the difference between muscle memory and conscious memorization. Today, I explain some of the techniques that I use to memorize music, and how these methods help me gain a greater understanding of the music that I play.

Memory Pillars

Music is cumulative. I’ve often made mistakes in the beginning of a piece during a concert, and it seemed like the whole piece was ruined. It’s a downhill slope, and many people find that just a few small errors in a situation where they are nervous will prompt an array of other problems. At this point, it’s mostly a mind game. However, it’s important to have the ability to rebound and come back from what hasn’t gone well so that it doesn’t affect the other parts.

I determine what parts of the music I know I can come to, without fail. I’ll call these places “memory pillars”: I can find them if I have a memory slip, or if I play something really badly. They may be 10 or so measures apart, or farther or closer depending on the music. I know that I am absolutely confident in my memorization at each memory pillar. Therefore, if the piece is just going horribly, I can reach one of these spots, put everything else behind me, and play confidently again. It sections off my the piece into memorizable chunks. That way, if something does go badly, it’s just a few measures that I mess up instead of the whole thing. This is especially helpful if you’re in tricky sections or places with a lot of notes. Sometimes it’s impossible to find where you left off, and your fingers run away from you! To avoid having to restart playing something, it helps if you have designated places that you know with 100% certainty that you can arrive at.

The best way to practice this and cement these memory pillars is to avoid playing the music from start to finish. Pick one of these spots, and practice starting there. Work backwards through the piece in chunks of measures. You should really be able to play from memory from anywhere that you start. You don’t want these places to sound any different, just feel comfortable starting from beginnings of phrases and know what to play there exceptionally well. Again, you’re training your brain and not your muscle memory here. You can convince yourself that whatever happens in a performance, you have a fresh start once you reach one of those pillars. Since you’ve practiced beginning at many places, you can imagine you are starting anew, and turn a bad performance into a better one.

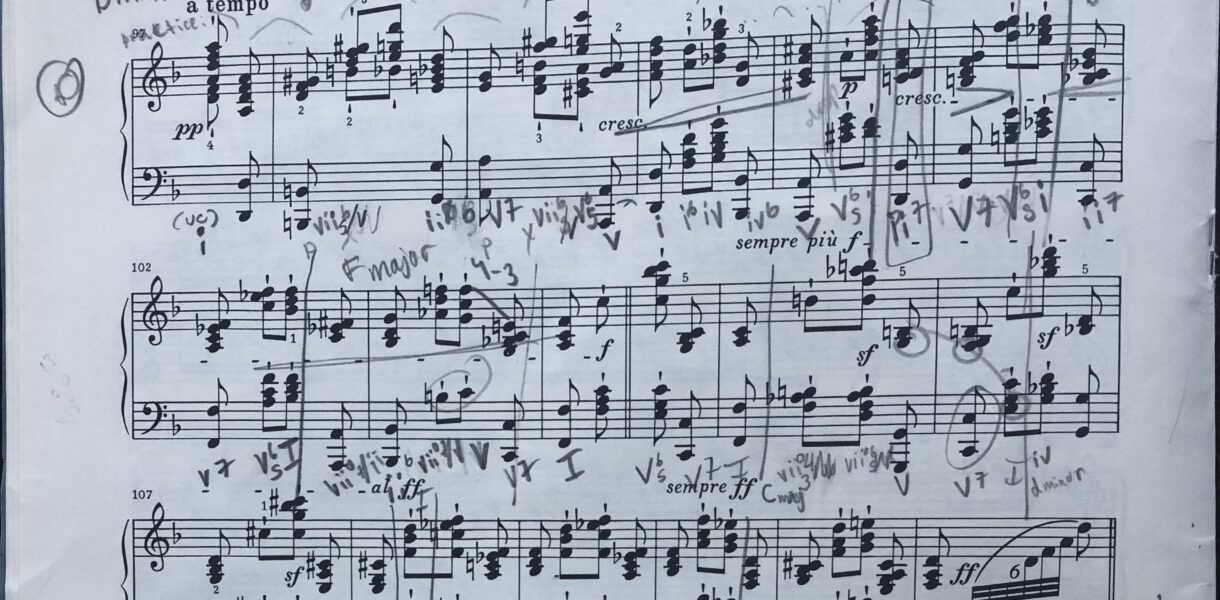

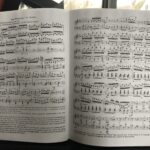

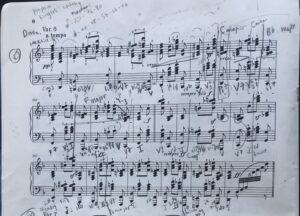

Analysis

This is one of my favorite things to do when I’m struggling to memorize something. I’m a total nerd for music theory, and I enjoy doing harmonic analysis of music. You can write down scale degrees, qualities and inversions, or if you’re not as familiar with music theory, just write in some chord names that you do know. The key to solid memorization? Actually understanding the music! And you’ll find that analysis will ultimately lead to a mature interpretation as well. I don’t do harmonic analysis of every part of every piece I’m playing, because that would take forever! I typically will look at troublesome sections, and I’ll do a full harmonic analysis of any baroque piece that I work on, because baroque music is all about the harmonies. And this method is helpful not only when there are blocked chords in the score. Most things always have underlying harmonies, even if “filler” scales or ornaments with non-chord tones exist over that harmony. If you play a string or wind instrument, look at the accompaniment part to determine the harmonies (you should definitely know what background harmonies are happening if your instrument is one in which you play only a single line, and you haven’t rehearsed with accompaniment yet – it’s necessary for complete understanding of the direction of the music as well). It will help you to understand when harmonies change, perhaps every half measure, full measure, or irregularly. If it’s solo Bach on a stringed instrument, think of implied harmonies, and do some analysis of those! The way you analyze the music isn’t very important, so do whatever feels comfortable and familiar. As long as you have something to give the music direction and shaping, and something that can be memorized, that is perfect. Another benefit of using this method is that if you mess something up and play some wrong notes because of a memory slip, it’s likely you’ll play notes that are chord tones, and there is less of a chance the audience will realize something went wrong.

Next, take a detailed look at the function of what you’re playing. Everything in music has purpose, and you have to figure out what the purpose is. Imagine yourself listening to the music instead of playing it. What would you expect to come next? Is this different from what actually happens? Are there notes that don’t fit with any of the chords you’d expect them to (e.g. raised or lowered tones)? Why does the composer do this? Music is often full of surprises, and if you think about it, you’ll find them. Just one example of this could be a deceptive cadence as opposed to the anticipated authentic cadence. You must remember what is least expected extra well – because while you should convey surprise to the audience, the last thing you want is to be surprised yourself. Music has patterns, so don’t fall in the trap if something is different. Why is it so difficult to memorize contemporary or atonal music? It’s because the chords we hear don’t fit the pattern that we expect. So, whenever possible, take advantage of patterns you can find, and remember the variations from these patterns as well.

This method of analysis can take quite a bit of time to do well. However, it’s really helping you practice, not just memorize. If you understand something, you’re able to make a better interpretation! This will give you a deeper understanding of the music you are playing. And, as you get in the habit of analyzing things as you look at them, you’ll become a better and more knowledgeable musician.

Structure and Comparison

A key aspect of understanding music is having an idea of musical form. Some music is predictable through form. For example, traditionally the first movements of sonatas written in the classical period as well as many other works are written in sonata-allegro form. An exposition will present themes and material to be developed, a development section will build, reconfigure, and expand on previous material, and the recapitulation will explore thematic material in the tonic key. Once patterns in structure can be found between different pieces, it becomes more approachable to memorize these large works.

Musical form lends itself naturally to sections that are parallel or contrasting. Also, sections can be very similar, but only slightly different! Sometimes the difference is so small that it’s difficult to tell just by practicing each section individually. Whenever I have a parallel section I’ll compare the score for both parts, and visually note the differences when I’m not playing. It’s important to be aware of different notes, different rhythms or lengths of notes, different spacing, different articulation, and different dynamics.

I don’t consider the formal structure of a piece the most important aspect of a piece of music. However, it can be a useful tool in memorizing and understanding music. Once there is a general idea of form, then specific phrases and their function in the bigger picture begin to make sense.

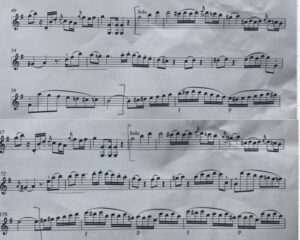

Pay Attention to All the Voices

Music is layered, and we tend to get confused with multiple voices or lines occurring at once. In polyphonic music, I have found it helpful to have a better understanding of each voice individually before I try to memorize all the voices together. When memorizing something on piano, I always make sure I have left and right hand memorized individually as well. If I can’t play left hand from memory without right hand, or vice versa, my memorization isn’t great because it’s dependent and conditional (and again, larger issues will occur if one hand plays something wrong). So, I always make sure I know all the different voices or lines on their own.

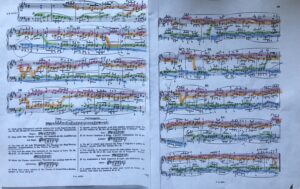

Fugues in particular are infamous beasts to memorize. Almost every pianist is acquainted with J.S. Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier, and while memorization in the preludes is pretty much straightforward, the fugues can cause much frustration. I will make a copy of my music, and in this copy I’ll color code different voices and work on them individually and in different combinations (e.g. I’ll play voice 1&4 together, then voice 2 & 4, etc.) so I really know what’s happening, as opposed to practicing more vertically as chords and then running into issues later with memorization. This is applicable outside of Bach, I’ve used this color coding/voice isolation method in the Shostakovich preludes and fugues, in Haydn sonatas, in Mendelssohn’s works, the list is endless.

Use your Brain

I have definitely been a part of the Avoid Using Your Brain club in the past. I’d like to say I’ve moved on to bigger and better things, but there are still times when I zone out. I’m also prone to focusing on the most trivial things instead of the things that deserve my attention. A nervous habit I have when I’m full of adrenaline is that I think too far ahead in the music I’m playing. I’ll doubt myself, and ultimately end up playing wrong notes, when really I should be present in the moment, thinking of phrasing and character.

Imagine something which I’m sure you’ve seen before: a young music student walks onto the stage at their very first recital, nervous and stone-faced, and they play their memorized piece lifelessly, as if they were a zombie. But this is often the truth with musicians of all ages, not just flustered children! It’s easy to think that once you’ve arrived at your concert or audition, your work is done and whatever happens happens. Not true! You need to have your brain working in its best state the whole time. And since you’ve been using your brain more to memorize music with these techniques, you’ll really need to consciously use your brain in a performance! Playing music can be mentally taxing, and this is the reason why after a recording session you’ll feel exhausted – the majority of it is mental, not physical. During the school year, I have very long music days on Saturdays between my personal practice and rehearsals for orchestra and chamber ensembles. By the time I’m done, my brain is fried so I never do my homework on Saturday nights. If you’re engaging your brain, it’s truly exhausting. One way I prepare for having my brain fully committed to a performance, and not wandering elsewhere, is to make sure I’m focused on music in all of my practice sessions. While you’re practicing something that doesn’t seem very exciting, it’s so easy to think of what happened with your friends yesterday, or what the weather is like … at this point, take a break and get back to focused practice afterwards. Efficient practice is much better than long, rambling practice. Sometimes I accomplish more in 1 hour than 4 hours of practice. If you’re not using your brain for music in practice sessions, there’s no reason your brain will be engaged for a concert. It leaves room for you to think about all the people in the audience or how nervous you are when on stage. Like anything else, being focused takes practice.

Vary your Practice to Have a Backup plan

When it’s all said and done, and you feel like you’ve memorized something to the best of your abilities, the plan is still not foolproof. Sometimes, your hands and fingers just decide to have a mind of their own. Because of this, you need to prepare for the unexpected. I like to practice other fingerings and bowings (and I believe the same would apply to breathing for other instruments) just in case something goes awry. Play with completely ridiculous fingerings and bowings just for fun and note what happens. Of course, this actually happening in a live performance is less than ideal, but it will lessen chances to mess up and will make you feel more confident – if you shift in the wrong spot, or switch fingers too early, you’ll have a backup plan! Still practice your chosen fingering the most so that you don’t get confused, though! See, I’m able to play a C Major scale on piano, for example, with any variation of fingers. I can use only my first 3 fingers – I’d rather not because it’s risky and doesn’t sound as good, but I can. If I totally botch the fingering I had planned, I’m able to play a different one because I’ve memorized the music, not just the motions. I’ve also been in a scenario where I cut open one of my fingers on a key during a concert and had to avoid using that finger entirely as I finished the piece. Varying your practice should also include changing the tempo and maybe practicing with different articulations or rhythms.

The ultimate goal is to prepare for the unexpected. It will only work to ease fear if you are able to know that you’ll be prepared against any surprises your brain throws at you.

These are just a few of the ways that I go about memorizing works for performance. However, these techniques help me to not only memorize the music, but to actually learn it in a way that’s thoughtful and long-term. These ways may not work for everyone, so I believe that all musicians should continually try to explore new ways to practice and ways to learn and memorize music that works best for them.